Church Slavonic language

| Church Slavonic | ||

|---|---|---|

|

(endonyms)

|

||

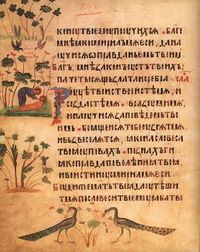

| Page from the Spiridon Psalter in Church Slavic |

|

|

| Spoken in | ||

| Total speakers | — | |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

|

| Writing system | Glagolitic alphabet (Glag), Cyrillic alphabet (Cyrs) | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | cu | |

| ISO 639-2 | chu | |

| ISO 639-3 | chu | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Church Slavonic (also Church Slavic) is the liturgical language of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Croatian Greek Catholic Church, Macedonian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church, Ruthenian Catholic Church, Serbian Orthodox Church and other Slavic Orthodox and Slavic Greek Catholic Churches, as well as the liturgical language of Croatian and Czech Church Slavonic Roman Catholic traditions. It was also the liturgical language of the Orthodox Church in Wallachia and Moldavia until the late 17th century.

Historically, this language is derived from Old Church Slavonic by adapting pronunciation and orthography and replacing some old and obscure words and expressions with their vernacular counterparts (for example from the Old East Slavic language). Attestation of Church Slavonic traditions appear in Early Cyrillic and Glagolitic script. Glagolitic has nowadays fallen out of use, though both scripts were used from the earliest attested period. The first Church Slavonic printed book was Croatian Church Slavonic Missale Romanum Glagolitice from 1483 in Croatian angular Glagolitic, followed shortly by five Cyrillic liturgical books printed in Kraków in 1491.

Contents |

Recensions

Various Church Slavonic recensions were used as a liturgical and literary language in other Orthodox countries — Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia — until it was replaced by national languages (but the liturgical use may continue).

Russian

Before the eighteenth century, Church Slavonic was in wide use as a general literary language in Russia. Although it was never spoken per se outside church services, members of the priesthood, poets, and the educated tended to slip its expressions into their speech. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was gradually replaced by the Russian language in secular literature and retained its use only in church. Although as late as the 1760s, Lomonosov argued that Church Slavonic was the so-called "high style" of Russian, within Russia itself this point of view largely vanished during the nineteenth century. Elements of its style may have survived longest in speech among the Old Believers after the late-seventeenth century schism in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Many words have been borrowed from Church Slavonic into Russian. While both Russian and Church Slavonic are Slavic languages, some early Slavic sound combinations evolved differently in each branch. As a result, the borrowings into Russian are similar to native Russian words, but with South Slavic variances, e.g. (the first word in each pair is Russian, the second Church Slavonic): золото / злато (zoloto / zlato), город / град (gorod / grad), горячий / горящий (goryačiy / goryaščiy), рожать / рождать (rožat’ / roždat’). Since the Russian Romantic era and the corpus of work of the great Russian authors (from Gogol to Chekhov, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky), the relationship between words in these pairs has become traditional. Where the abstract meaning hasn't commandeered the Church Slavonic word completely, the two words are often synonyms related to one another much as Latin and native English words were related in the nineteenth century: one is archaic and characteristic of written high style, while the other is common and found in speech.

In Russia, Church Slavonic is pronounced in the same way as Russian, with some exceptions:

- Church Slavonic features okanye and yekanye, i.e., the absence of vowel reduction in unstressed syllables. That is, о and е in unstressed positions are always read as [o] and [jɛ]/[ʲɛ] respectively (like in northern Russian dialects), whereas in standard Russian pronunciation they have different allophones when unstressed.

- There should be no de-voicing of final consonants, although in practice there often is.

- The letter е [je] is never read as ё [jo]/[ʲo] (the letter ё does not exist in Church Slavonic writing at all). This is also reflected in borrowings from Church Slavonic into Russian: in the following pairs the first word is Church Slavonic in origin, and the second is purely Russian: небо / нёбо (nebo / nëbo), одежда / одёжа (odežda / odëža), надежда / надёжный (nadežda / nadëžnyj).

- The letter Γ is read as voiced fricative velar sound [ɣ] (just as in Southern Russian dialects), not as occlusive [ɡ] in standard Russian pronunciation. When unvoiced, it becomes [x]; this has influenced the Russian pronunciation of Бог (Bog) as Boh [box]. In modern Russian Church Slavonic occlusive [g] is also used and considered acceptable; however Бог (nominative) is pronounced "Boh" [box] as in Russian.

- The adjective endings -аго/-его/-ого/-яго are pronounced as written ([–aɡo], [–ʲeɡo], [–oɡo], [–ʲaɡo]), whereas Russian -его/-ого are pronounced with [v] instead of [ɡ] (and with the reduction of unstressed vowels).

Serbian

In Serbia, Church Slavonic is today generally pronounced according to the Russian model. The medieval Serbian recension of the Church Slavonic ceased to be used in the early eighteenth century, when it was replaced by the Russian recension. The differences from the Russian variant are limited to the lack of certain sounds in Serbian phonetics (there are no sounds corresponding to letters ы and щ, and in certain cases the palatalization is impossible to observe, e.g. ть is pronounced as т etc.).

Ukrainian

The difference between Russian and (Western) Ukrainian recensions of Church Slavonic lies in the pronunciation of the letter yat (ѣ). The Russian pronunciation is the same as е [je]/[ʲe] whereas the Ukrainian is the same as и [i]. Greek Catholic variants of Church Slavonic books printed in the Latin alphabet (a method used in Austro-Hungary and Czechoslovakia) just contain the letter "i" for yat.

Grammar and style

Although the various recensions of Church Slavonic differ in some points, they share the tendency of approximating the original Old Church Slavonic to the local Slavic speech.

Inflexion tends to follow the ancient patterns with few simplifications. All original six verbal tenses, seven nominal cases, and three numbers are intact in most frequently used traditional texts (but in the newly-composed texts, authors avoid most archaic constructions and prefer variants that are closer to modern Russian syntax and therefore are better understandable by the Russian-speaking people).

The fall of the yers is fully reflected, more or less to the Russian pattern, although the terminal ъ continues to be written. The yuses are often replaced or altered in usage to the sixteenth- or seventeenth-century Russian pattern. The yat continues to be applied with greater attention to the ancient etymology than it was in nineteenth-century Russian. The letters ksi, psi, omega, ot, and izhitsa are kept, as are the letter-based denotation of numerical values, the use of stress accents, and the abbreviations or titla for nomina sacra.

The vocabulary and syntax, whether in scripture, liturgy, or church missives, are generally somewhat modernised in an attempt to increase comprehension. In particular, some of the ancient pronouns have been eliminated from the scripture (such as етеръ /jeter/ "a certain (person, etc.)" → нѣкій in the Russian recension). Many, but not all, occurrences of the imperfect tense have been replaced with the perfect.

Miscellaneous other modernisations of classical formulae have taken place from time to time. For example, the opening of the Gospel of John, by tradition the first words written down by Saints Cyril and Methodius, искони бѣаше слово "In the beginning was the Word", were set down as въ началѣ бѣ слово in the Ostrog Bible of Ivan Fedorov (1580/1581) or in the recently used Elizabethan Bible (the first printing in 1751).

See also

External links

- Orthodox Christian Liturgical Texts in Church Slavonic

- Bible in Church Slavonic (iPhone / iPod Touch)

- Bible in Church Slavonic language (PDF texts in Church Slavonic; webpage in Russian)

- Problems of computer implementation (Russian)

- Full Russian Church Slavonic Dictionary (with Old East Slavic words) (Russian)

"Slavonic Language and Liturgy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Slavonic Language and Liturgy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.- Church Slavonic Keyboard Online

|

||||||||||||||||||||